Lessons We've Learned

Many aspects of Lifewater's current strategy stems from lessons we've learned along the way. Here are some real-life stories, and what they taught us.

"Dignity Kits" lead to girls' increased school attendance

One of the key benefits of drilling a well and making safe water easily accessible is increased school attendance. When children no longer need to spend hours each day walking to and from distant ponds and creeks for water for their families, they can be in their classrooms.

We monitor school attendance and almost always see it increase after a new well is available, or an existing well is operating again.

However, that wasn't happening at several schools in Kenya in 2023 after we provided, through our ongoing partnership with STADA Kenya, the students and staff with safe, accessible water. Attendance improved among the boys but not among the girls. Why?

That led to Lifewater helping STADA Kenya recruit and train several women to sew washable (therefore re-useable) sanitary pads. The pads are now part of "Dignity Kits" that STADA distributes during Health and Hygiene classes that STADA offers at schools and in other community settings as water projects are completed. In the photo to the left, girls are showing their kits.

After the introduction of the Dignity Kits, we've been delighted to see Kenyan girls regularly in school attendance. Another lesson learned!

Rainwater harvesting and storage — for sanitation needs only

Most of the systems (including 10,000-litre storage tanks) have been installed at schools or in other community settings, while other smaller systems have been located alongside people's homes.

The original intent was that the stored water would be used for both drinking and sanitation needs. But during an evaluation in 2023 and the first part of 2024, we concluded that many schools, communities, and sometimes families weren't keeping the storage tanks clean enough for the water coming from them to be considered safe for drinking.

In response, we have begun encouraging schools, communities, and families to use the water from their tanks only for operating toilets, hand-washing, and other sanitation needs.

Meanwhile, we still welcome donations for rainwater harvesting and storage systems, but with the understanding that the water from them is for sanitation -- which is still vital for human survival -- rather than for drinking.

Many COVID-19 lessons

COVID-19 taught us a variety of lessons.

When the pandemic interrupted supply lines and caused fuel shortages in Haiti in 2020, we began stockpiling drums of fuel to protect ourselves against future emergencies.

When the pandemic interrupted supply lines and made it almost impossible for us to buy small quantities of hand pumps in Nigeria, we ordered enough pumps in India to fill an entire 40-foot shipping container. This long-term investment in inventory, and others like it, will ensure a much more secure supply and enable us to receive large-volume discounts from key suppliers.

Also, when the pandemic interrupted supply lines and made it impossible for us to receive a long-overdue order of essential polymer compound for drilling wells in Liberia, we opted to order and send by courier a very small supply that filled the gap until the larger order could finally arrive.

And when the pandemic slowed our well-drilling activities due to the fuel and inventory shortages we were suffering, we realized the importance of being able to quickly pivot towards more pump repairs and towards additional partners. In early 2021, we signed an agreement with a non-government organization to begin drilling wells and repairing pumps in Nigeria.

Ultimately, COVID-19 reinforced in us the importance of being ready to quickly adapt to a changing environment, including directing resources towards protective masks, cleaning solutions, etc., so our overseas staff could save lives in the communities they are serving.

When social distancing made it difficult for large numbers of people to gather for our health and hygiene training that accompanies water projects, we held smaller classes and checked the body temperatures of participants before the training began. Our drilling and repair teams also wore masks and practiced social distancing. Like the rest of the world, we adapted!

Stockpiling knowledge

Not all the lessons Lifewater has learned about how to operate more effectively have occurred overseas. Some have happened back home in Canada. The most painful of them stemmed from the death of Jim Gehrels, Lifewater Canada's president and co-founder.

Jim and Lynda strongly believed in having a good digital filing system, and invested many hours in documenting processes, procedures, and lots of other Lifewater essentials — including long-term strategic plans. But when Jim died, Lynda and the Lifewater board suddenly realized how much Lifewater knowledge had died with him.

She was left struggling to, for example, understand his plans (and preliminary discussions with supplier) for a new Lifewater database. During the next few months, Lynda contracted an expert to work with the supplier in developing a database that will carry Lifewater into its next level of growth and development.

What everyone at Lifewater learned from Jim's tragic passing is the importance of constantly documenting and updating information so that if a member of the team can't carry on, the information is there for others to continue.

Lifewater's leaders are focused on making the "new" team structure even very robust and durable — including through cross-training everyone on important tasks, and regularly updating strategic plans — to be well-prepared for the threat of losing a key member or other potential crises.

The trained bandits

Pump Repair Technicians must be trained within the context of the village in which they live. Any financial or material compensation must be negotiated between them and their neighbours. Here's how we learned that lesson.

After the Liberian civil war that ended in 2004, an aid group received substantial international funding to teach job skills to "demobilized ex-combatants" or former soldiers so they could earn a living. The decision was made to train some of them as Pump Repair Technicians. For weeks, they were trained on how to use tools, how wells work, and how to take apart and repair every known Afridev hand pump problem.

The funder and aid group were happy to successfully complete a major development initiative. The former fighters were happy to be transitioned into a new career. Everyone was happy -- until the last day of school when they were handed diplomas and learned there were no jobs. The surrounding villages already had their own Pump Repair Technicians and didn't need more.

Eventually, Lifewater and other aid groups developed a metal security jacket which locks to the pump to cover all the bolts

In the meantime, Pump Repair Technicians are still needed more than ever to help address the worldwide problem of pumps sitting broken. But training must happen not in a diploma-issuing school, but in village settings where there is a mutually agreed-upon need for a technician and a plan for him or her to be hired and paid.

Ongoing support and training, such as that gained through the "guided pump repair model," (see the "Superhero' story below) will ensure that technicians gain the experience they need to keep safe water flowing in their communities.

The missing spoon

In 2010, a remote village community in Haiti reported problems with their pump. Pastor Job had to drive down the mountain on his motorcycle to alert us, and the Lifewater team had to come the next day with their truck, crew, and supplies.

Assessment of the pump indicated no major issues, and routine maintenance was performed. The following day, Job again showed up and said the pump was still giving trouble. The team went back the next day, removed the pump head and pump rod and checked the plunger assembly and sealing rings. The pump was re-assembled, tested, and pumped water. The team went home.

The next day Job showed up yet again. The team returned one more time and this time removed the entire pump, even cutting and pulling out the rising main, cylinder, and associated foot valve. When the last piece of rising main was pulled out of the well, they turned it upside down . . . and out fell a long piece of metal! One of the village mothers shouted "THERE is my missing spoon!"

Confession time followed, revealing that her son Samuel and his friend Josue had been playing with the pump. Josue lifted the pump handle all the way up, exposing a small slot by the bearing. It took some effort, but Samuel managed to push a spoon all the way until it fell inside the pump.

Over the course of a few days, the spoon gradually worked its way down the rising main until it reached the bottom of the well. There it became stuck in the foot valve, causing it to be jammed in the "open" position. With vigorous pumping, the spoon would sometimes float up -- releasing the valve and allowing the pump to operate normally. But then the spoon would sink and jam the foot valve open again.

Over time, the spoon bowl broke off, leaving a jagged metal tip on the handle. This rubbed up and down against the pump cylinder, scratching it beyond repair.

Five minutes of children's play caused two weeks of water disruption for an entire community. A $5 lock would have prevented a $1 spoon from requiring more than $300 in labour, fuel and pump parts. The entire experience underlined again for us the importance of having wells and pumps securely locked when not needed for community use.

The cactus innovation

In Haiti, they have a great word — “dégagé” — which means "figure it out and make it work with whatever you have on hand." This often requires impressive ingenuity and innovation.

In 2010, a well was drilled in Haiti in memory of Katie, a Canadian water expert who died in the earthquake. The community was very poor, but had been asked to build a fence around the well to keep cows and goats from depositing dung by the well and causing damage by rubbing up against the pump.

When Lifewater volunteers went back the following year to audit this project, they could not get to the well until they found the caretaker. He had carefully transplanted cactus plants in a circle around the well, and then used a few boards to install a lockable gate. Site access was most definitely controlled without placing an inordinate financial burden on the community.

May we all be inspired to practice “dégagé” to make our development work more innovative and affordable!

You don't roast a dog quickly

In 2010, Lifewater Canada co-founder Jim Gehrels was having an increasingly frustrating overseas trip. Time was ticking down to his return flight home, and his efforts to bring about change for good increasingly felt like trying to push a rope!

At the end of his wits, Jim phoned a local friend who had pastored churches through difficult times. Anthony came and patiently listened as Jim poured out his frustrations. When Jim finally ran out of words, it was time for Anthony to respond. After reflecting for a while, he said "Brother Jim, you don't roast a dog quickly." That was all Anthony said!

Puzzling advice indeed! Cultural differences were highlighted as Anthony explained that everyone knows cat meat is sweet to eat, but dog meet is oily and tough. If you try to roast the dog quickly, the outside burns and the inside remains oily and unpalatable. To do it right, you put the dog on a spit over a low-heat coal fire for an entire day. Then the oil drains out, the meat cooks all the way through, and it makes a good stew over rice.

Anthony said most community leaders know this, and so they watch in dismay as aid groups come in with aggressive timelines trying to effect profound change in societies that have evolved over hundreds of years. Relationships that gradually build trust are the ones most likely to achieve effective partnerships and cooperative projects.

You don't roast a dog quickly. It's an insightful image for sustainable development that has helped guide the work of Lifewater for many years now!

Cascading pump failure

In Liberia, there are four communities in Margibi Country -- two on each side of the Marshall Highway. Each community used to have about 500 residents. Lifewater helped provide safe drinking water in this area by drilling one well in each of the four communities. All the wells were located within a two-kilometer radius of each other.

These 1,000 people then all walked down the road to village #3 to draw water from their well. Having 1,500 people pumping from the one well was far too many, and that pump soon broke down. All these people then went to the last pump in the area. There were non-stop line-ups and this pump quickly wore out from the overuse.

One community failing to fix its broken pump started a chain reaction that quickly led to the entire area losing its access to safe drinking water. Lifewater named this phenomenon "Cascading Pump Failure."

With no functioning pumps, all 2,000 residents of the four communities reverted to fetching drinking water from stagnant swamps. This continued for several months until a Lifewater team was finally alerted to the situation. All the pumps required simple repairs which were completed in a day for just $100!

Cascading pump failure will not occur if a community has a maintenance plan in place, takes immediate action to repair a broken pump, and has an alternate source of water to draw from while their primary pump is being repaired.

The adjacent towns could have protected their supply by having a trained Well Caretaker, by locking the pump after their water had been drawn, and by having their Pump Repair Technician help the first community to fix its broken pump before others started failing.

Grinding rock -- and teeth!

During the Liberian civil war between 1995 and 2004, all Lifewater wells were drilled with the LS100 drilling rig. This lightweight unit is relatively safe for new drillers to use, can be easily carried in a pickup truck, and can create good water supplies in many places.

During well audits in 2007, we noticed that many of the wells being drilled were increasingly shallow. This is understandable as workers were paid by the number of wells completed, and wells were completed faster and with less physical effort if they were shallow. However, more and more wells were being found where residents complained that there was no water during March and April — the two hottest months of the year.

The Lifewater drillers were told to keep drilling. The rig bounced around and progress was measured in inches per hour. The frustration of the drill team mounted, and soon they were grinding their teeth and saying this effort was pointless.

Then at 55 feet, they broke through the hard rock layer that had been impenetrable to local well diggers. The borehole was terminated at 60 feet with an impressive yield of eight gallons per minute!

To this day, this is the only well in the area that does not go dry in the hot season, and many other communities have benefited because the drillers have applied lessons learned there to go deeper in other communities than the local hand-dug wells that don't provide water year-round!

A spoonful of death

In 2007, Lynda Gehrels (now Lifewater Canada's president) used her 35 years experience as a Registered Nurse to help prepare Health and Hygiene lessons to share during her first trip to Liberia. But all her preparation didn't prepare her for what would transpire in the middle of her disease transmission class.

Twenty-five men and women, with several toddlers and a few babies wrapped around their mom's bodies, attended the three full-day training sessions. The information was simple in concept -- offered through skits and stories using photos, and presented with constant individual participation required. There was lots of hands-on training, and by the end of the second day, people were getting very comfortable with each other.

"I was sharing again how unsafe drinking water was the reason why so many suffered from running stomach (diarrhea), with the wee ones and the elderly especially prone to getting ill and often dying," Lynda recalls. "It was a lesson I had covered numerous times before, but this time I noticed one of the older women in the class start to silently cry, tears running down her cheeks.

"Later, I shared a taxi home with her daughter-in-law. Her tears started to fall as she explained that in the class, her mother-in-law had realized that the tradition to give every one-month-old baby in her family their first drink of water had directly led to the death of two of her grandchildren. They had spoken together after the class and she had found the strength and faith to forgive her mother-in-law. My tears were the only consolation I could offer as I listened to the grief and pain in her words.

"My second trip to Liberia painted a bright rainbow around that painful memory. I met with these two women and they were so happy to share their success story. While they were visiting a relative, a child had gotten very ill with diarrhea, and the village was far from a clinic. But they were able to use the information they'd learned in the workshop and the child was able to regain his strength and live.

"Although it didn't dim the sadness (of the two grandchildren's deaths), it offered some balancing joy that this life would be spared to grow and bloom! That's pretty great fruit from a simple hygiene lesson!"

The daily bucket race

In Northern Kenya, communities are small and isolated. To obtain a high school diploma, students must attend boarding schools. At the schools, chores are divided among students.

When Lifewater Canada president Lynda Gehrels visited the school four years later, she was greeted by a puzzling sight: bushes and fences near the well were covered in upside-down buckets. The mystery was solved when the end-of-day school bell rang. The school doors burst open and spewed out girls in a full sprint for the "bucket trees." The first to grab her bucket was the first in line for the pump!

Each girl was required to fill two buckets every morning for her hygiene and drinking needs for the day. Each girl was also required to fill another bucket at the end of the school day for mopping and cleaning washrooms, the dining hall, kitchen, dorm hallway, classrooms, etc.

All the girls arrived at the pump at the same time, and so even when everyone was pumping quickly, the morning line-up lasted nearly four hours! Girls started pumping water as early as 4:00 a.m.! Some ate supper cold because they were near the back of the after-school line.

It clearly highlighted the need for a second well to meet this school's peak water needs.

The widows' well

By 2005, Lifewater had learned the importance of pump ownership. As part of the deliberate shift to community investment and commitment to long-term project maintenance, Lifewater no longer put any sponsorship information on wells. Putting sponsor names or dedications on wells unintentionally identified those names as the well owners.

Earlier that year, two elderly widows decided to sponsor a well in memory of their beloved husbands. They sent in the sponsorship funds, and then went one step further by wanting to go to Kenya to see the well and participate in its dedication.

The well was drilled, the widows flew to Kenya and were thrilled to see the well and meet the people who were receiving the safe drinking water. As part of the well dedication ceremony, they showed everyone large framed photos of their husbands, told the villagers about the men, and then placed a memorial plaque beside the pump. They came back to Canada thrilled with the whole experience.

A few months later, Lifewater received a panicked phone call from the women. They had just received a long-distance phone call from the villagers who were calling to inform the widows that their husbands' pump was broken, and could they please come back to Kenya to fix it!

Our Kenya team helped fix the pump, but it took years for the villagers to adjust their thinking from the well being owned by those white-haired Canadians to the well being owned by themselves. Even after the widows died, the villagers still did not consider the pump as their own.

It was only when a "Deed of Pump Ownership Transfer" with official stamps and seals was made and delivered to the village chief did they finally take responsibility for maintaining the pump!

The superhero!

We started training Pump Repair Technicians in Liberia in 1995. However, lack of repetitive experience and of spare parts often led these technicians to simply call the Lifewater office to send a repair crew, rather than trying to do the work themselves.

In 2005, some Lifewater volunteers, dressed in their Sunday best, were walking down the Bensenville Highway to a church service. They were flagged down by some women who said their pump had broken down the day before and they needed to get water for their families.

By pumping the handle, the volunteers realized the problem was not serious and could be solved without extra parts.

The Lifewater volunteers offered to talk David through the repair process. He agreed but started his work very tentatively. The volunteers had him take one part off the pump, then put it back on; then take it off again while also taking off a second part, then putting them both back on; then taking three parts off and putting them back on . . . with each repetition David became faster. By the time he got down to the problem, he was working confidently.

When the pump was put back together, the local women pumped the handle and fresh cool water can pouring out! The women went wild, hugging and cheering David like he was the town superhero! He had an ear-to-ear grin!

No one even heard or responded to the Lifewater volunteers as they said farewell and headed off to church -- leaving the superhero chatting with the excited women as they filled their buckets! And the seed for the idea of "guided pump repair" was planted.

Chaos at Ma Sarah's school

In 2004, there was a school in Paynesville in Liberia needing a well. One of our conditions for providing a well by the school was that it would also provide safe water for surrounding residents. This agreement sounded fair, and everyone was happy to get the water. The school janitor, Ma Sarah, was trained as the Well Caretaker and the well was successfully drilled.

As word of the good-quality water spread, crowds of women with buckets continued to grow. At its best, the school yard became a place for loud laughter and animated social gatherings. At its worst, the yard was a place for intense arguments, threats and altercations. Teachers had trouble teaching because of the loud noise outside their classroom windows, and at recess, the children's playground was increasingly spoiled.

It became impossible for Ma Sarah to take care of her janitorial duties, monitor the pump, and control the people. She finally exercised her Pump Caretaker authority and took decisive action. The pump was locked from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. with the exception of short openings for students during recess. Community members could draw water before and after school, but if the yard was unacceptably soiled, there would be no community access to water.

Teachers could now teach. Students had cool water at recess. Ma Sarah could peacefully clean the school. And neighbourhood women began to police each other's activities rather than be without access to the water their families needed.

This is pretty much as close as you can get to a "happily ever after" ending!

The lions will eat you!

An even more memorable story about the importance of community involvement in determining where a well will be drilled comes from Kenya. Lifewater Canada's Harry Oussoren was there to help villagers who had to walk very far for safe drinking water.

With a very generous donor funding his work, Harry rented a big rig and tried drilling where the community wanted him to -- at the top of a big hill close to their houses. Despite long hours of drilling to great depth, the borehole was dry. The rig was moved over with the same result. And the third attempt was also unsuccessful.

So Harry tried to explain some hydrogeology. He talked about aquifers and that at the bottom of the hill, they would not have to drill as deep to find the water table. Again, the community leaders said the well could not go there.

Harry tried one more time -- finally raising the issue of his depleted budget and how the most likely place to find water would still be at the bottom of the hill. Again the leaders said the well could not go there.

Finally Harry lost his temper and demanded: "Why can't the well go there?"The chiefs said "Because the lions who live there will eat you." They found a better location for the well!

Too many men!

In 2004, a well was planned for the Margibi area but local women objected when they saw the drilling team setting up in the town square.

It turned out that the time spent gathering water was an important social gathering for those women. Away from husbands and children, they could share and encourage each other without being overheard.

The well location was changed to near a big tree just out of sight of the village huts. The women did not have to walk far, but could still have their private time to relate together.

The disappearing pump

In parts of northern Haiti, development can be quite dense and there is very little land available on which to drill a water well. Following the devastating 2000 earthquake, there was limited community consultation and Lifewater teams gladly drilled wells on whatever land was offered.

In 2004, Lifewater volunteers who were auditing wells in Haiti had a problem. One of the wells that had been drilled several years earlier had disappeared! First the team thought that maybe the pump had been stolen so they looked through tall grass for the borehole and pad. The GPS coordinates told them they were in the right area, but there was no sign of the well.

Then a gate in the wall of the adjacent private home opened -- and the team found their missing well! it hadn't moved. But after the well was originally drilled, a landowner built a security wall around his property -- which included where the well was. The well effectively "vanished" as a source of communal water for surrounding residents. The landowner was a powerful political figure, and no one dared protest to him or to complain to Lifewater.

After discussions with Lifewater, the landowner agreed to have his watchman keep the gate open for two hours in the morning and two hours in the afternoon for surrounding residents to come and draw water.

This taught us the importance of spending time and effort to be assured that land on which we drill is communal land, with a small parcel being severed off for this purpose if necessary. Since then, no further problems like this have arisen.

The vanishing latrine

Simple colorimetric test strips can make a profound impression. In 1999, Lifewater volunteers were working in a community in Ghana. During the training workshop, the local well was tested. It was found to contain elevated levels of nitrate and nitrite -- clearly related to a latrine located right beside the well.

Facility leaders were shown the dark colours on the test strips. They asked what it meant and were told that the latrine was contaminating the well and that an infant drinking water from it could get sick to the point of death.

The workshop then resumed but communication was difficult due to loud, rhythmic pounding. During a break the volunteers went outside and found the source of the noise. The latrine was being torn down, even while the workshop was still in session! Education can mobilize people and bring about needed change!

Just because water is safe to drink doesn't mean people will want it

In 1997, Lifewater wells along the Marshal highway in Liberia were audited and the water was found to contain noticeable concentrations of fine sand. The water was safe to drink but the sand made it unappealing. The sand also rubbed against the pump seals, causing premature pump failure.

In 1999, several wells in Liberia's Dwazon area were audited by volunteers and the pumps were found to be in great shape because they were not used. The well water had noticeable hydrogen sulphide odours. The water was safe but no one was interested in drinking water that smelled like rotten eggs!

Similarly, in 2004, Lifewater volunteers visited a cluster of wells in Kakata, Liberia. The water tested as safe to drink. But the villagers had reverted to using water from the stagnant swamp because the well water had high iron concentrations that gave it an oil-like sheen and made it bitter to drink.

Stinky socks

In 1995, Lifewater was asked by the European Union and the Liberian government to conduct the first systematic testing of 150 communal wells in the capital city of Monrovia. Lifewater found that nearly every well had active bacterial populations, with half showing the presence of coliform and/or pathogenic bacteria.

When we presented these alarming findings to village chiefs and government leaders, to our disappointment, they responded with ambivalence and a lack of concern. Most saw no problem with people continuing to drink from unsafe wells, and/or with disinfecting wells with woefully inadequate quantities of chlorine.

Meanwhile, for entirely different reasons, tension was developing between two Lifewater volunteers. They were sharing a room and starting to accuse each other of stinky socks and poor hygiene. Then one of them opened the closet door and found the problem -- half a dozen forgotten bacterial water samples!

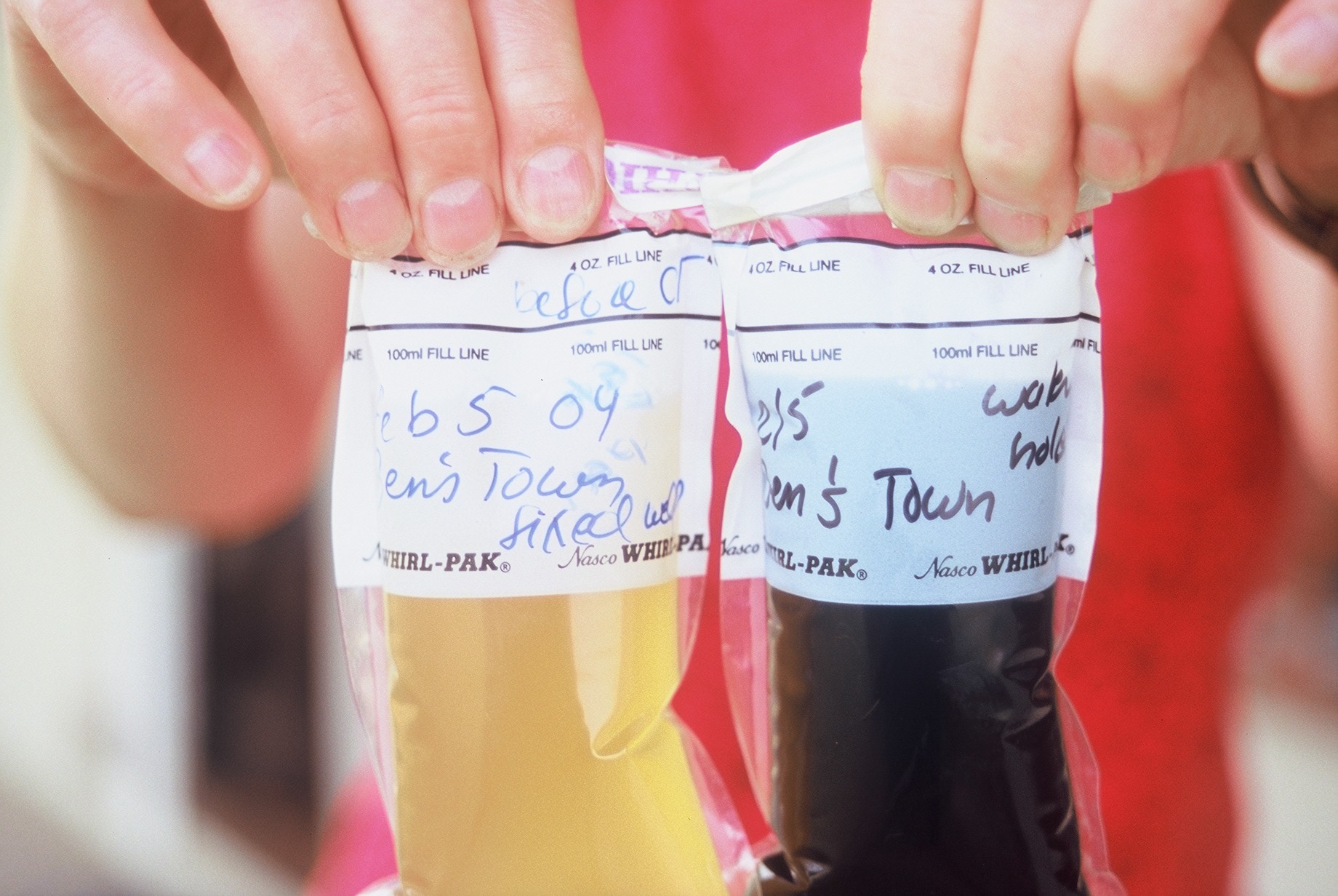

One of our volunteers who'd been trying to convince the village chiefs and government leaders that their wells were too hazardous for people to be drinking from them decided to set aside science and go with "show and tell." He showed the chiefs and villagers the discolored, smelly water samples.

Having uncontaminated and contaminated water samples side-by-side brought instant understanding. People stopped drinking from the wells and started asking what to do. As one person succinctly put it: "We cannot give that black death to our children!" Now there was widespread local support for properly disinfecting wells, rehabilitating dormant wells, and drilling new wells.

From this, we learned the importance of showing people contaminated water samples so they can see the "black death" colour and smell the "stinky sock" odour. It gets everyone's attention!

"Your" well is broken

From 1995 to 2004, Liberia was racked by bloody civil war. During this time, wells drilled by Lifewater Canada were gifts, fully funded by donors. Villages did not have to contribute to the new project.

In 2004, the war was over and a team of volunteers was helping drill a well along the Robertsfield Highway. Nothing went right, and it was a long, frustrating process.

To end the week on a positive note, the team decided to visit a village where a well had been drilled two years earlier. They envisioned being greeted by happy parents, playing children, and safe water flowing from the well.

When the team arrived, the pump was draped with drying laundry and the pump pad was parch dry. The chief greeted the team with a scowl instead of a smile, and angrily asked: "Where have you been? Your pump has been spoiled for many months now and our children are getting sick from drinking the swamp water again!"

Sure enough, the team watched women coming back with coloured water from the stagnant swamp. But they also saw dried fish for sale at roadside stalls and new soccer nets on the community play field. Clearly, there was a disconnect between spending priorities and health impact.

Further discussion revealed that the villagers believed the pump belonged to Lifewater and not to them. They had no sense of ownership and felt like it was not their property. This was a watershed moment for Lifewater as the team members realized that if they covered the cost of fixing the pump, it would be used until it broke and then sit unused until they came again. This was emergency relief rather than sustainable development.

When the chief came back, he said the Lifewater plan to come back in four months was "no good". Instead, the town would have the money saved in only one month, so they wanted the repair team to come back then!

When we returned and repaired the pump, the chief asked if his town could pay $20 in advance so when the pump broke again, the team could bring parts and fix it right away! This led to the start of a "pump insurance" program in Liberia that enables communities to sign paperwork and pay a flat yearly fee so Lifewater workers will repair a pump whenever it breaks.